Americans talk about being “tethered” to their smartphones mostly from the standpoint of the time suck that’s involved and the tendency to miss what’s going on around us when we’re supposed to be working, spending time with family or friends, or (let’s hope not) driving down the highway. It’s hard to resist the offerings on your smartphone which now is millions times more powerful than NASA’s computers from the 1960’s.

Americans talk about being “tethered” to their smartphones mostly from the standpoint of the time suck that’s involved and the tendency to miss what’s going on around us when we’re supposed to be working, spending time with family or friends, or (let’s hope not) driving down the highway. It’s hard to resist the offerings on your smartphone which now is millions times more powerful than NASA’s computers from the 1960’s.

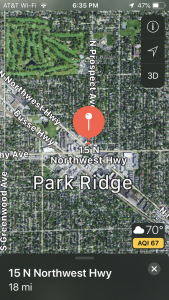

But one result of all that tethering – whether we’re texting, streaming music, getting directions from our GPS, or posting on social media – is that our smartphone is silently, relentlessly gathering all kinds of information about us. Your smartphone knows where you are, how you got there, with whom you’ve been communicating, and what you’ve been typing into your favorite search engine lately. It is this geolocation feature of smartphones that lets parents and spouses know the location of their family members, but it also provides a wealth of information to law enforcement personnel and those who understand how to retrieve this information. It has been quietly used by law enforcement agencies to obtain data about what smartphones have been active near crime scenes by issuing a subpoena to Google to recover the data. This was a feature story in the New York Times on April 13, 2019 which is part of an ongoing examination of the privacy issues associated with smartphones.

Although many people are vaguely uneasy about the variety and volume of information they cough up in their various apps, ultimately they are too tapped into the convenience and entertainment aspects to worry about controlling how much of their data is falling into the hands of marketers, retailers, the government and even foreign governments. Not to mention the brain cell and social skills deterioration that takes place.

Even if they cared enough to try, the average person does not have anywhere near the technical knowledge to outsmart these apps and somehow escape the gaze of faceless technology companies sifting through their information. But the lure of being told when to steer down a certain street or the ability to store all the passwords you can’t remember has proven too seductive, anyway.

Having said all that, Americans might want to at least consider awakening from their catatonic states before data-hungry tech companies delve even deeper into their lives as smart phones track even more data and provide the ability to perform functions like facial recognition. We should all probably start getting at least a little paranoid and consider what guardrails we do and don’t need – what could reasonably fence off a little privacy without imposing undue burdens on startup tech companies.

The General Data Protection Regulation of 2018 put into place by the European Union has provided individuals with considerably more power over how their personal data is collected and put into use, and it’s led to stiffer punishments for companies that suffer data breaches. The GDPR also contains rules on how people can be targeted by advertisers that might raise free speech concerns in the U.S.

While some have argued that GDPR goes too far, the state of California last year passed the Consumer Privacy Act, which has been criticized by some observers for not going far enough. The act requires California-based companies to strengthen data protection, and the legislation provides consumers with more knowledge and power over how their data gets used, levying fines on tech platforms that fail to comply.

The effects of the California law remain uncertain because it does not go into effect until next year, and there may yet be amendments to it. At least 10 other states are in various stages of passing such privacy bills. What will happen next and how this will play out are to be determined. But you can probably get alerts about it on your smartphone.

Chicago Business Attorney Blog

Chicago Business Attorney Blog