Americans talk about being “tethered” to their smartphones mostly from the standpoint of the time suck that’s involved and the tendency to miss what’s going on around us when we’re supposed to be working, spending time with family or friends, or (let’s hope not) driving down the highway. It’s hard to resist the offerings on your smartphone which now is millions times more powerful than NASA’s computers from the 1960’s.

Americans talk about being “tethered” to their smartphones mostly from the standpoint of the time suck that’s involved and the tendency to miss what’s going on around us when we’re supposed to be working, spending time with family or friends, or (let’s hope not) driving down the highway. It’s hard to resist the offerings on your smartphone which now is millions times more powerful than NASA’s computers from the 1960’s.

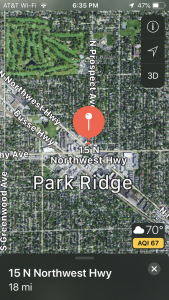

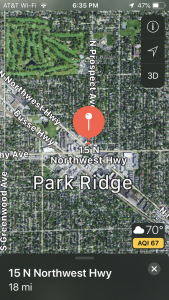

But one result of all that tethering – whether we’re texting, streaming music, getting directions from our GPS, or posting on social media – is that our smartphone is silently, relentlessly gathering all kinds of information about us. Your smartphone knows where you are, how you got there, with whom you’ve been communicating, and what you’ve been typing into your favorite search engine lately. It is this geolocation feature of smartphones that lets parents and spouses know the location of their family members, but it also provides a wealth of information to law enforcement personnel and those who understand how to retrieve this information. It has been quietly used by law enforcement agencies to obtain data about what smartphones have been active near crime scenes by issuing a subpoena to Google to recover the data. This was a feature story in the New York Times on April 13, 2019 which is part of an ongoing examination of the privacy issues associated with smartphones.

Although many people are vaguely uneasy about the variety and volume of information they cough up in their various apps, ultimately they are too tapped into the convenience and entertainment aspects to worry about controlling how much of their data is falling into the hands of marketers, retailers, the government and even foreign governments. Not to mention the brain cell and social skills deterioration that takes place.

Chicago Business Attorney Blog

Chicago Business Attorney Blog